How pet parents keep their cool

Featured

How to Turn Your Vacation Into an Opportunity to Help Local Rescue Animals

Split your time sipping cocktails by the beach and being a “voluntourist” for puppies and kittens in need.

7 Things I Wish People Knew About My Deaf Dog—and Why You Should Adopt One

On Specially Abeled Pets Day, I’m finally saying what I’ve been thinking since the day I brought my pup home.

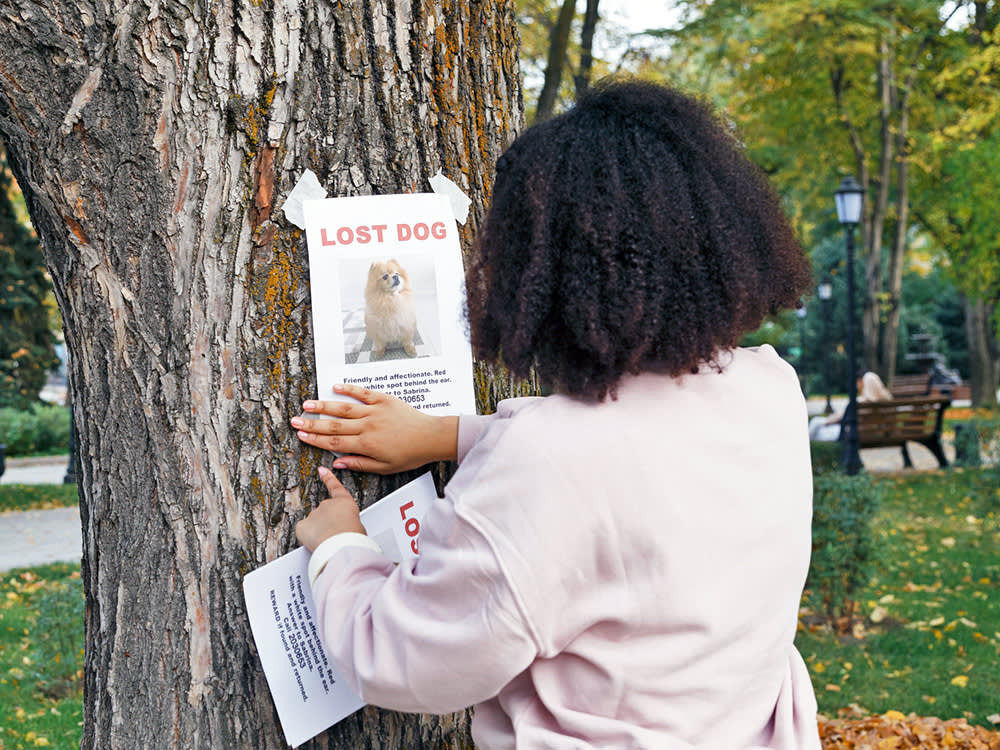

2 Million Dogs Are Stolen in the U.S. Every Year — And It’s Causing Trauma

New study finds having a dog stolen feels like losing a child.

News

- health

- health

- lifestyle|To the Rescue

Got a new pet? Here’s what to do.

Let’s be real. Welcoming home a new dog or cat is a very cute but very crazy time. Thankfully, we’re here to help with a nifty new pet parent to-do list.

Get Startedopens in a new tab

A Month Spoiling a Rescue Pit Bull on a $75,000 Income—Mugs With Her Face on Them Included

opens in a new tabPetty Cash is a new series where we find out just how much real people are spending on their pets.

Read more, then submit your own story!opens in a new tabThe Latest

It’s Kismet: John Legend and Chrissy Teigen Launch a Lifestyle Pets Brand

The parents of four dogs put their in-home “focus group” to good use on this collab with the Street Vet.

Is Pet Jealousy a Thing? What to Do When a Pet Likes One Person in a Relationship More

Or perhaps one partner just thinks the cat or dog is getting all the attention.

Can Cats Eat Cucumbers?

We already know they’re scared of them, thanks to all those YouTube videos.

Most Popular

- lifestyle|Heavy Petting

- behavior

- lifestyle

- lifestyle

- lifestyle

- lifestyle

Ask a Vet

Pet health question that’s not an emergency? Our vet team will answer over email within 48 hours. So, go ahead, ask us about weird poop, bad breath, and everything in between.

Health & Nutrition

Why Does My Cat Drool?

Dogs rule, cats drool. Like, that’s normal, right?

Dogs rule, cats drool. Like, that’s normal, right?

Two Georgia Dogs Died After Consuming the Toxic Sago Palm

It looks cute, but this plant is incredibly deadly to dogs. Here’s everything you need to know.

It looks cute, but this plant is incredibly deadly to dogs. Here’s everything you need to know.

Behavior & Training

Kristi Noem Says Her Dog Was “Untrainable”—Here's Why That’s Not True

As a behaviorist, the South Dakota governor's actions horrify me for several reasons.

Your Dog Takes Forever to Find a Place to Poop Because of This Scientific Phenomenon

Your pup is a compass, but only when they are doing their business.

Your pup is a compass, but only when they are doing their business.

Yes, It’s True: Study Says Cats Love People Who Don’t Like Cats

It’s not all in your head.

It’s not all in your head.

Get your fix of The Wildest

We promise not to send you garbage that turns your inbox into a litter box. Just our latest tips and support for your pet.

Lifestyle

How Long Should You Grieve Your Dog Before Getting a New One?

Here’s some advice as you struggle to make this hard decision.

The Perfect Cat for Every Astrological Sign

Are you a good match for an extroverted, social kitty — or a little Miss Independent?

Are you a good match for an extroverted, social kitty — or a little Miss Independent?

Is Pet Bereavement Leave in Our Future?

More companies are considering how they can support grieving pet parents.

More companies are considering how they can support grieving pet parents.

Shopping

27 Mother’s Day Ideas For All the Cat Moms Who Secretly Want a Gift

Custom ceramics, whimsical puzzles, feline-themed kicks, clutches, candles, and more.

21 Mother’s Day Gifts That Dog Moms More Than Deserve

Custom pet portraits, adorable sweaters, self-care essentials for both mom and pup, and more.

Custom pet portraits, adorable sweaters, self-care essentials for both mom and pup, and more.

5 of the Best Flea and Tick Preventatives and Treatments for Dogs in 2024

Treatments to ward off transmission this spring and summer.

Treatments to ward off transmission this spring and summer.

Animal Welfare

Congress Orders the Department of Veteran Affairs to Stop Testing on Cats and Dogs

Under new legislation, all experiments on dogs, cats, and primates must end by 2026.

Why Kitten Season Is Getting Longer and More Intense Every Year

And what you can do to help.

Los Angeles Bans New Breeding Permits Due to Shelter Overcrowding

Local lawmakers think breeding has gotten out of control.

New Dog Training 101

Look, new dogs are cute. But they’re also little alien monsters who have descended to destroy our furniture and our sleep. Still, we love them. Luckily, this program covers all the basics, from potty training to proper socialization—all through positive reinforcement. Time to stock up on treats!

Start Trainingopens in a new tab

Our editors and experts created the ultimate guide to the best products in pet care. Check out the winners—and snag some discounts too.