How pet parents keep their cool

Featured

LA Residents Could Get Paid to Foster Pets

A new program aims to reduce overcrowding in shelters.

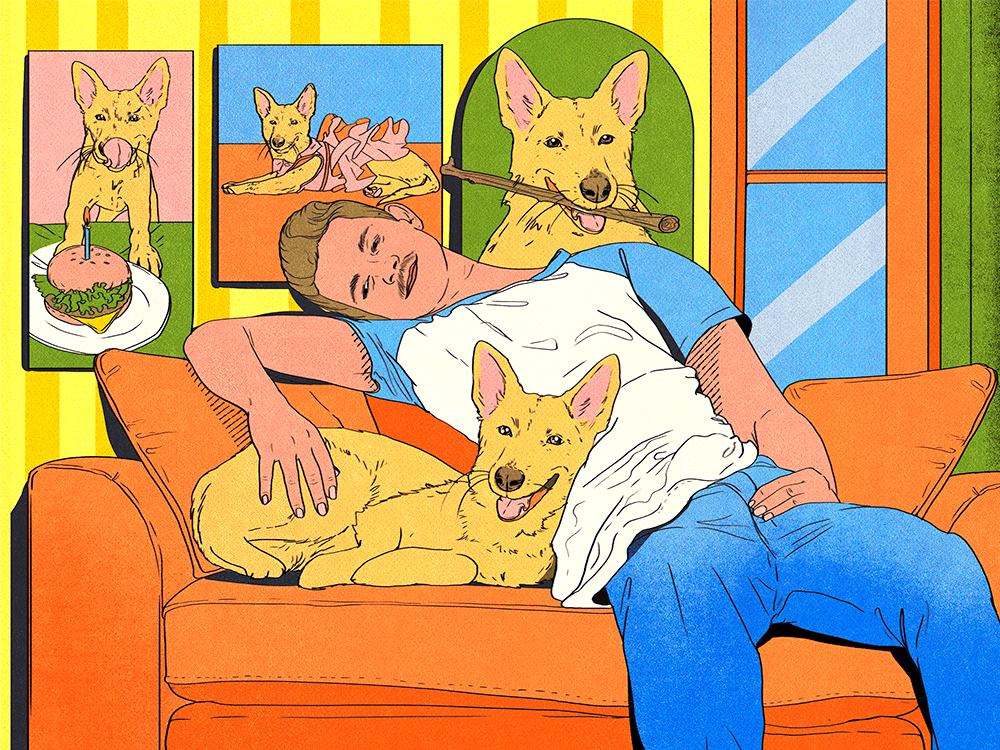

A Month Spoiling a Rescue Pit Bull on a $75,000 Income—Mugs With Her Face on Them Included

From dry shampoo to bandanas in spring pastels, this upstate New York pet dad gives his foster fail the good life.

News

- lifestyle|To the Rescue

- lifestyle

- health

Got a new pet? Here’s what to do.

Let’s be real. Welcoming home a new dog or cat is a very cute but very crazy time. Thankfully, we’re here to help with a nifty new pet parent to-do list.

Get Startedopens in a new tabThe Latest

The Perfect Cat for Every Astrological Sign

Are you a good match for an extroverted, social kitty — or a little Miss Independent?

Tom Holland Pays Tribute to His “Lady”—His Late Dog, Tessa

The Staffordshire Bull Terrier was a beloved member of the actor’s family for 10 years.

Most Popular

- health

- behavior

- lifestyle

- shopping

- lifestyle|Heavy Petting

- behavior

Ask a Vet

Pet health question that’s not an emergency? Our vet team will answer over email within 48 hours. So, go ahead, ask us about weird poop, bad breath, and everything in between.

Health & Nutrition

Can Dogs Get Pimples? Causes, Symptoms, and Treatments

Time to go to the doggie dermatologist!

Time to go to the doggie dermatologist!

5 Plants That Are Toxic to Your Dog

Thriving plants are spring’s whole thing—but these offenders can be perilous to pets.

Thriving plants are spring’s whole thing—but these offenders can be perilous to pets.

Behavior & Training

Why You Shouldn’t Be Skeptical of Positive Training Methods

It is powerful enough, even for the tough cases, and it is the best choice—here’s why.

It is powerful enough, even for the tough cases, and it is the best choice—here’s why.

Yes, It’s True: Study Says Cats Love People Who Don’t Like Cats

It’s not all in your head.

It’s not all in your head.

Get your fix of The Wildest

We promise not to send you garbage that turns your inbox into a litter box. Just our latest tips and support for your pet.

Lifestyle

What Does Your Love Language Say About You as a Pet Parent?

We all give and receive love in our own way, pets included.

8 Dog Hiking Services That’ll Take Your Pup on a Nature Adventure For You

Most dogs can benefit from taking a walk on the wild side.

Most dogs can benefit from taking a walk on the wild side.

Your Comprehensive Guide to Eco-Labels on Pet Products

Here are the sustainability buzzwords you should look out for on the packages of your fave products.

Here are the sustainability buzzwords you should look out for on the packages of your fave products.

Shopping

21 Mother’s Day Gifts That Dog Moms More Than Deserve

Custom pet portraits, adorable sweaters, self-care essentials for both mom and pup, and more.

11 Eco-Friendly Pet Grooming Products

Package-free brushes, plant-based wipes, certified-organic shampoos, and more.

Package-free brushes, plant-based wipes, certified-organic shampoos, and more.

What Are the Best Dog Nail Clippers?

Finally—you won’t dread at-home grooming time.

Finally—you won’t dread at-home grooming time.

Animal Welfare

Congress Orders the Department of Veteran Affairs to Stop Testing on Cats and Dogs

Under new legislation, all experiments on dogs, cats, and primates must end by 2026.

Why Kitten Season Is Getting Longer and More Intense Every Year

And what you can do to help.

Los Angeles Bans New Breeding Permits Due to Shelter Overcrowding

Local lawmakers think breeding has gotten out of control.

New Dog Training 101

Look, new dogs are cute. But they’re also little alien monsters who have descended to destroy our furniture and our sleep. Still, we love them. Luckily, this program covers all the basics, from potty training to proper socialization—all through positive reinforcement. Time to stock up on treats!

Start Trainingopens in a new tab

Our editors and experts created the ultimate guide to the best products in pet care. Check out the winners—and snag some discounts too.